2020 has been a year of uncertainty.

It’s always kept us at arm’s length, never revealing its hand: a garrulous con artist hinting at going straight. Of course, when I first walked into the hospital back during the glorious days of late spring, nobody could tell you, if you had Coronavirus. Or if you would catch it. Or quite how you could avoid it.

Would you catch it while marching against the murder of George Floyd, or on the bus, at school or at the races. Grace, a midwife at the Whittington Hospital, told me how after she caught it, she wasn’t sure if she had it. But by the time she couldn’t get out of bed to collect the shopping her friends had dropped off for her, she was sure she had it. And then, she wasn’t quite sure if she would survive it. She knew she didn’t have the strength to answer the phone calls from her family, and she felt isolated, and scared of death: “I could not sleep because I could not breathe, and was afraid of sleeping in case I could not wake up. So I was always there, sitting on my bed day and night.”

Joy

She is a straight backed sort of woman, with a graceful and soft smile. She sits cleanly in front of me, with no clouds in her eyes as she talks about her potential death. Being both a midwife and the co-ordinator of the labour ward, I imagine she’s seen it all, and her soft voice doesn’t falter as she talks, “I don’t feel angry, no, not at all.”

The shiny floors and off white walls of the hospital don’t seem to allow much for anger. It’s not the kind of emotion I encounter. There’s too much professionalism and too much starch, but the oily gauze of uncertainty seems perfectly suited. In normal times, the tight air juxtaposed between corridors and cotton nightgowns seems to invite hushed tones. The swoosh of passing beds keeps everyone on their toes, and now, there’s certainly more knife in the air.

Mukesh

Joy expressed it well. “I remember one day coming to work and I was crying,” though she’s not the sort really. Her family know her as someone who will do what she needs to do. I can imagine her tears taking her aback, but given the amount of “dying, dying, dying”, it’s not down to her personality.

There are just so many circumstances. For Joy, working in housekeeping, it’s the closeness of being intimate with someone – feeding them spoon by spoon, and then returning from a break and finding they’ve died. Instead she trusts to the ginger that her husband brings back from the outside world once his Sainsbury’s delivery shift is done. They drink infused tea each night.

Henrietta

But if you remember back then, it wasn’t just your personal circumstances. I like how Charlie puts it: “I’m worried about what’s happening in Vietnam and Japan.” It’s also the rising cases in Brazil: “I’m concerned about the whole world.” But how can you cope with that on the outside, and all of the deaths on the inside? How do you stop from bring it all back home to roost?

Cleveland

Lizzie was seconded into ITU. I imagine that most people smile when they think of her. She’s graceful and, I would guess, very kind. It was the end of the day, and the end of her shift when I met her, and the usually quiet corridors had pretty much emptied out. I was fussing because I was looking for a place to photograph her, and like a dog trying out different beds, I couldn’t quite make my mind up. I was worried that I was taking up too much of her time doing nothing. Once I’m settled, she tells me of her sleepless nights and bad dreams. She tells me how she still hears the beeping machines in the quiet of her bedroom. And she tells me how she’d repeat the events of the day, in the hope of doing better the next.

Lizzie

The weight of it all bears down, and the ungovernable uncertainty screws it in tight. What can we do with all this grief? Can it be shipped off like plastic waste, or need we carry it in our boots?

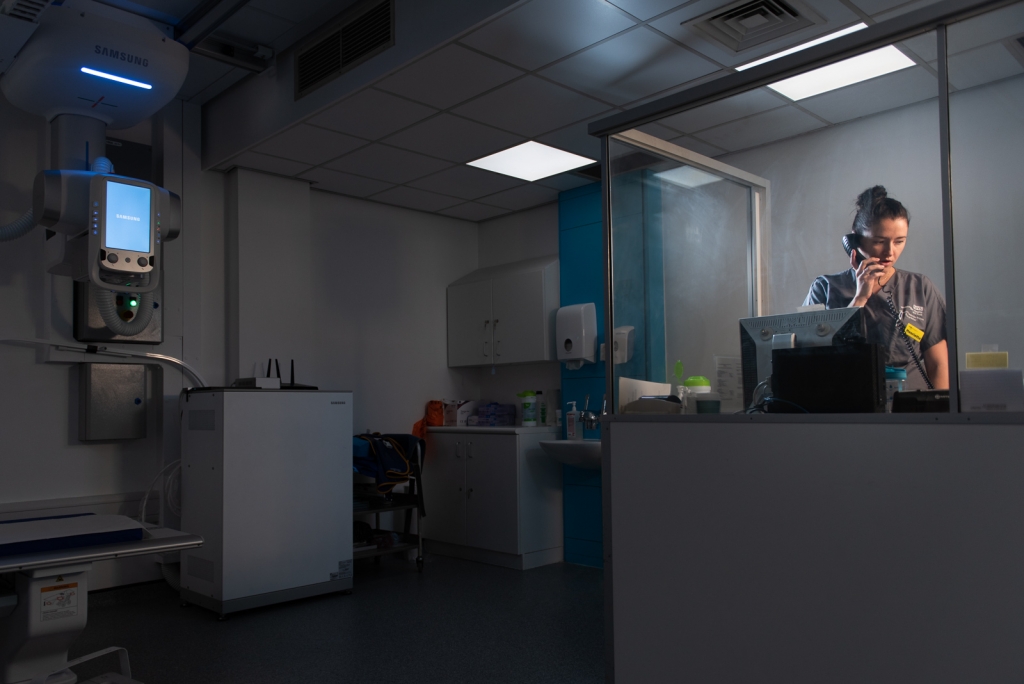

Sometimes people didn’t want to talk. On an x-ray, Covid produces what looks like white bubbles: “it’s like circles, white circles all around the lungs” Henrietta says, leaving me with the feeling of the finest filigree etched in ice. She talks to me in the darkened imaging room, waiting for the next person who won’t be long. She’s a radiographer, tall, and with an open face. I can imagine her striding down to the ITU when called, mobile unit in tow. She needs to get all of her PPE on before going in. “We try to find our patient, because it is a bit crowded, and then we set everything up. Usually the patients are unconscious so we ask somebody to come and help us hold the tubes, lift the patients up or sit them up, and then we have this board which we put underneath the patient, bring the camera, and then we have the image.” It’s a very good bet that the delicate white bubbles meet her gaze, though there’s no way of guessing when, or when not. As always, uncertainty stalks the halls like Grendel’s mother.

Charlie

One of the porters in the hospital died from Covid. Nick Joseph. Cleveland, a tall fellow with a thick Jamaican accent, tells me how he saw him on the Wednesday and then was told on the Monday that he’d died. “That just hit me right here, in the heart you know.” He’s standing down in the subterranean reaches of the hospital, but he’s shining none the less. “You’re given a choice in life.”

Of that he’s certain.

Rachel

Mukesh, another porter, is sitting on one of the empty beds strung out along one side of the corridor at my asking, to take his portrait. The ITU and theatres are the next stop further down the passage, and people in scrubs, hats and Crocs pass at varying speeds. For him, it’s been a very intense time, and the way that he thinks of his family has changed. “I think of what my father always taught me, a long time ago,” and now he doesn’t stop on the way home.

Of course, there’s no where open for him to stop on the way home, but that’s not the point. A bit like how Rachel says “I feel like my bad days are the days where you see a lot of different people, but treat the same thing,” there’s an inevitability sometimes to the cadence of life, and the metronomic sigh of amnesia. Talking of life, she says “it’s so small. You forget it’s so precious.”

Thayanithy, Grace

Thayanithy, a wonderfully small and round lady, is standing in a sunny spot and jokes with me about how her husband, a veteran of three heart attacks, greets her back home with a bucket and mop, so keen is he to keep things clean. She scoots past him, up into the bath, leaving him to get on with it. You can feel the warmth of their relationship in her eyes as she chuckles, and when I meet her next in some corridor or other, she leans in close and asks me how I am.

Charlotte

In truth, I’m fortified by my stay at the hospital. The air has been kind to me, and it feels like the stolid weight of 2020 might yet be countered by the population of this small urban town. I warmed to Charlotte immediately, and felt easy with her natural manner. She tells me “we can’t hide something that’s an inevitable part of being a human – pain is inevitable. But the suffering, that’s the layer that we add. How we respond to it is what leads to the suffering.”

As Cleveland says, you can always be certain of having a choice.